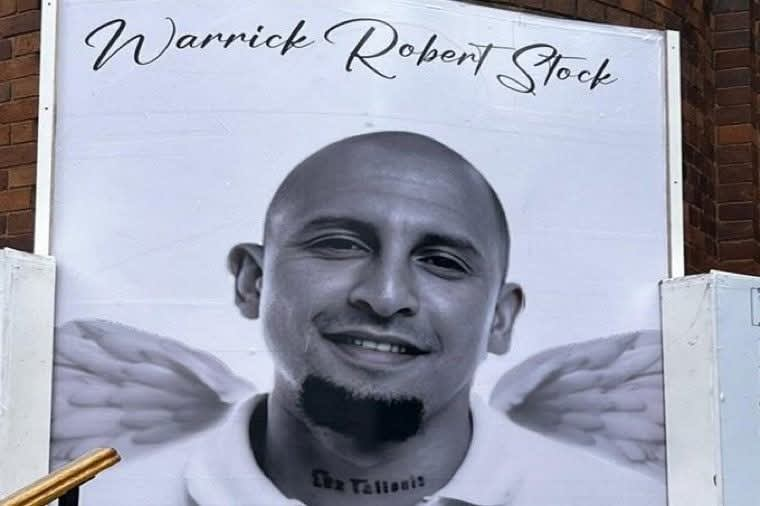

Nkosana Makate

Nkosana Makate’s fight against Vodacom reveals the quiet cruelty of South Africa’s justice system — a place where truth is measured in invoices. After decades of litigation, the inventor of “Please Call Me” faces a R13 million legal bill, showing how justice often favours those who can afford its price.

In this country, justice is a cathedral where only the wealthy can afford to light candles. The rest of us stand at the doorway, holding our small offerings, belief, patience, the hope that truth might be enough. But truth, as Nkosana Makate has learned, is not enough when the courts have price tags for prayers.

Makate’s story began with a simple act of imagination. In 2000, as a trainee accountant at Vodacom, he dreamt up a message for the voiceless “Please Call Me”, a lifeline for those who could not afford to speak first. It was an idea born out of South African reality, where airtime was a luxury and communication a small rebellion against poverty. But the dream became Vodacom’s gold mine, and Makate became its ghost.

He fought quietly at first, then legally, demanding recognition for his creation. The company dismissed him. Years turned into court files, affidavits, and media summaries. In 2016, the Constitutional Court finally said what should have been obvious, that Vodacom owed him compensation and must negotiate in good faith. For a moment, it felt as though David had struck Goliath right between the eyes.

But justice in South Africa does not walk in straight lines. In 2019, Vodacom offered him R47 million, a number that sounded large but was small compared to what his idea had earned them. Makate refused. Then in February 2024, the Supreme Court of Appeal (SCA) gave him new life, ordering Vodacom to pay between 5 and 7.5 percent of all revenue generated by the “Please Call Me” service since 2001, plus interest. Billions. A sum that said: ideas matter, even when they come from the bottom of the corporate food chain.

Vodacom, unsurprisingly, appealed. And in July 2025, the Constitutional Court, the same court that had once opened the door for Makate, closed it again. It set aside the SCA’s decision, sent the matter back, and ordered Makate to pay Vodacom’s legal costs. R13 million. R13 million reasons for the ordinary man to never challenge power again.

This is where justice becomes performance art for the privileged. A play written in the language of Latin and fees. Makate stands at its centre, not just as a litigant but as a lesson, that truth without wealth is an empty petition. The judiciary, with all its grandeur and robes, sometimes becomes a theatre where fairness is rehearsed, but seldom performed.

For seventeen years, Makate has been in courtrooms while others have been in boardrooms, cashing in on his idea. Lawyers, experts, analysts, they have all eaten from the same case, billing hours while the inventor counts years. Justice, it seems, feeds everyone except the one who needs it most.

And yet, Makate endures. His resilience is an act of defiance. It is the stubborn pulse of a man who refuses to be buried beneath legal paper. His case is no longer about money; it is about the architecture of inequality within our courts. When the cost of appealing becomes higher than the value of the claim, who is justice really for?

Makate’s fight mirrors a truth we whisper about but rarely confront, that South Africa’s courts, though open to all, are accessible only to some. To challenge power, one must first afford the price of participation. To stand before the bench, you must first survive the billing.

The government has a role to play. If we are to restore faith in justice, there must be structural mercy, funds to support public-interest litigation, protections for individuals who take on corporations, and reform in how courts allocate costs. Justice should not be a luxury item, available only to those who can afford the legal fuel to reach it.

Consumers too can speak. They can turn outrage into solidarity, refuse Vodacom’s silence, and run campaigns demanding that Makate be paid what is due. Every time someone sends a “Please Call Me,” they can remember the man who created it, unpaid and unrecognised, still fighting for his share of the sentence he wrote for all of us.

In the end, Makate’s struggle is not only his own. It belongs to every South African who has stood outside a courtroom, knowing that truth alone will not open its doors. The judiciary remains our Goliath, magnificent, necessary, but often deaf to the cost of entry.

And so, Nkosana Makate stands not as a victim but as a mirror, reflecting the shape of our justice system back to itself, a reminder that fairness without accessibility is only decoration, that justice without compassion is only law.

When David faced Goliath, he had five stones and faith. Makate has truth and debt. And still, he fights.