Mamelodi Cousins

There are mornings when South Africa smells of gunpowder and grief. When dawn arrives, it is not with birdsong but with the crack of gunfire — that sharp, merciless punctuation mark at the end of yet another woman’s life.

There are mornings when South Africa smells of gunpowder and grief. When dawn arrives, it is not with birdsong but with the crack of gunfire — that sharp, merciless punctuation mark at the end of yet another woman’s life.

Sunday was one of those mornings, the kind that splits open the soul of a nation and leaves it bleeding.

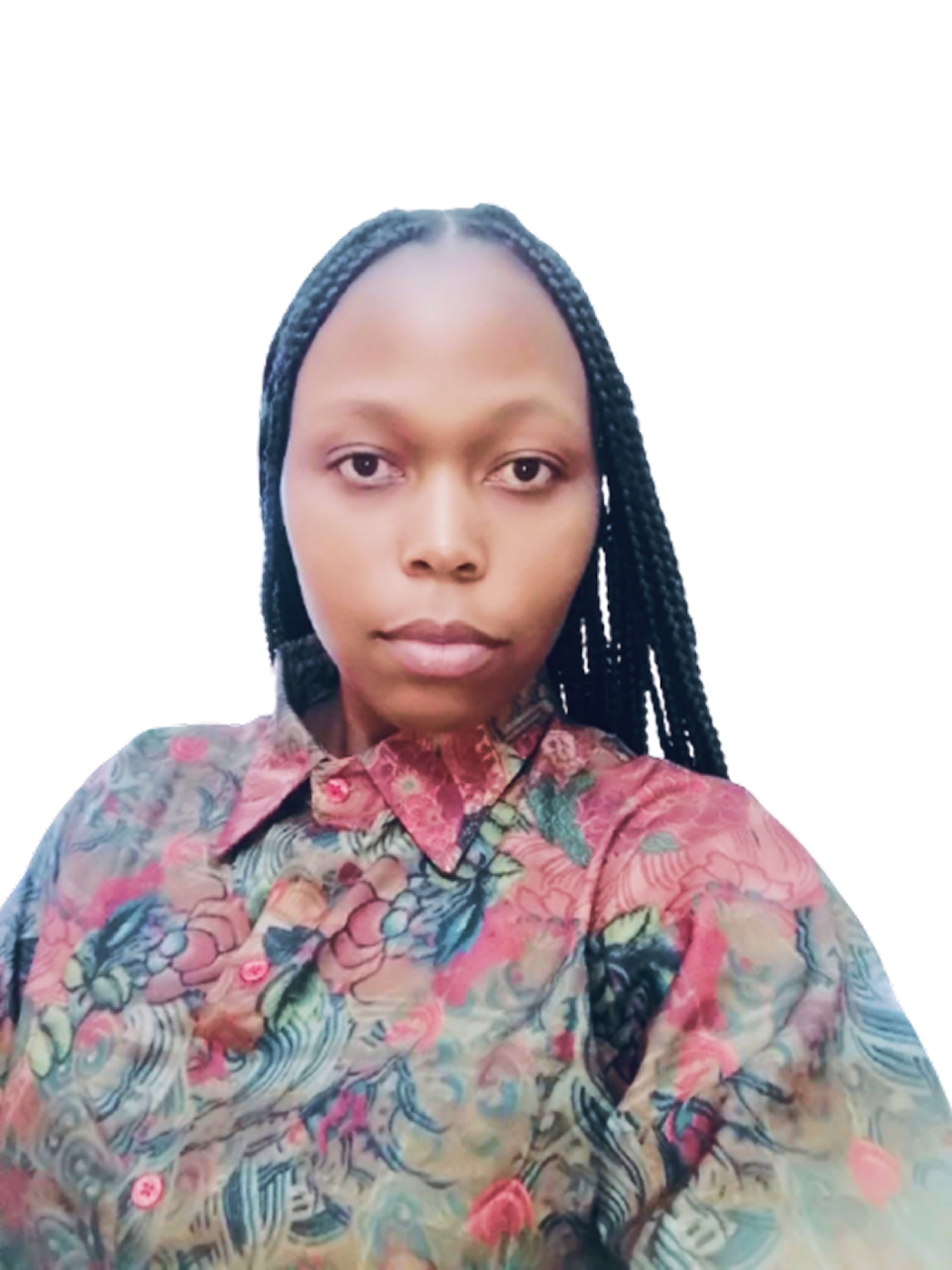

In Mamelodi East, two young cousins — Tshiamo Moramaga, 22, and Baleseng Moramaga, 21 — were found lying side by side on the street, both with gunshot wounds to the head. Execution-style. Not a robbery. Not a hijacking. Just the cold, deliberate extermination of two young women who dared to live.

Tshiamo, a beauty therapist whose hands were made for care, and Baleseng, a teaching student who wanted to mould young minds, were silenced before sunrise. Their names now lie scattered on the pavement of Mamelodi — another sacrifice in a country that devours its daughters and calls it destiny.

Neighbours say there had been an argument just before the shooting — that fragile hour between night and day when tempers are raw and reason thin. One of the cousins was heard arguing with what is believed to be a partner. Moments later, the quiet exploded into gunfire.

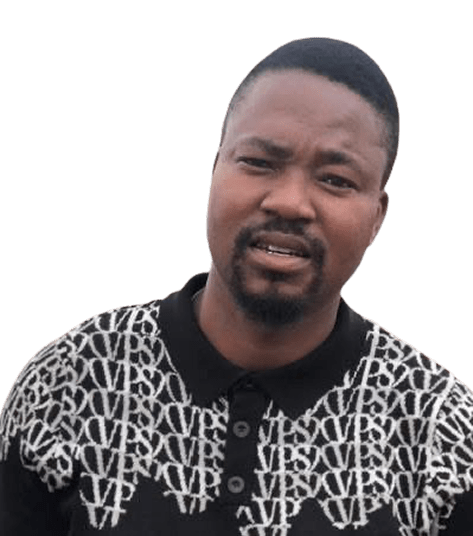

By Monday, police had arrested a thirty-eight-year-old man believed to be linked to the murders. Swift work, they said. But arrest does not undo absence. Arrest does not bring back futures ripped from the world. Arrest is a word on paper, while the streets still smell of blood and despair.

Tshiamo was a beauty therapist. She worked with her hands to craft beauty, to ease the burdens of others, to shape small moments of joy. Baleseng was a teaching student, one of those women who carried within her the quiet revolution of knowledge, the hope of generations. Both were alive with potential — and both were dead before sunrise. Their bodies, lying in a street in Mamelodi, are now just another line in a ledger, another statistic in a nation that bleeds its women like it is routine, like it is destiny.

And yet, we continue to whisper the old, dangerous lie: If you spend enough time with a violent man, he will eventually kill you. It is an odious sort of logic, one designed to shift blame from the hand that holds the gun to the body that bears it. As if women wander through life like archaeologists, turning over the wrong stones, stumbling into death by accident. No. Women do not die because of proximity. They die because they are born into a society that has some twisted men who believe that women are possessions, property, collateral damage — something to break when they refuse, when they resist, when they exist outside of expectation.

South Africa is a man who raises his fists and his children with the same hand, who teaches them that control is love, that fear is obedience, that a “no” is a sin punishable by violence. When poverty collides with this teaching, when guns are cheap and conscience cheaper, the body of a woman becomes the canvas upon which rage is painted. The result is this: cousins shot in the street, futures stolen, mothers crying in the dust of a dawn that promised nothing but grief.

We bury women. Or rather, we stack them. We count them in statistics, in hashtags… hashtags dressed as activism. We clap for the vigils, the marches, the campaigns — and then we step back into our lives, lulled by the illusion that words, alone, are enough. South Africa smiles at the world, calls itself a democracy, and then buries its daughters in silence.

Imagine it: the crack of gunfire bouncing off the walls of houses, the harsh echo swallowed by concrete and asphalt, followed by the scream of a mother who realises her child will never come home again. Imagine her running down the street barefoot, collapsing beside the still, broken body she once held in her arms. That sound — that raw, visceral cry — is the anthem of this country, louder and truer than any national hymn.

We tell women to be careful. To dress differently. To choose differently. To pray differently. But nothing, nothing, can save a woman in a country that has trained some of its sons to believe that women are obstacles, prizes, punishments, and nothing more.

Yes, the man is behind bars now. But do not mistake containment for justice. Justice would be a country where men like him could not exist, where entitlement could not translate into death, where women could say no and still see tomorrow. Justice would mean a society that values its daughters more than it tolerates its monsters. But here, justice is a ghost hovering over every headline, never materialising.

How many more names must we recite before we stop pretending this is random? How many funerals before Parliament recognises that this is not a crisis, but a civil war — a war against women, sanctioned by centuries of silence? We do not need hashtags. We do not need vigils. We need a revolution of rage, institutionalised, written into law, codified into culture. Until then, the streets will drink from the veins of daughters.

Tshiamo and Baleseng should have lived. They should have argued about hair, rent, food, about nothing at all. They should have grown old, laughed, loved, and failed in peace. Instead, their lives were terminated for nothing more than existence. Their blood stains the pavement, their futures stolen, their laughter silenced. And still, the country steps around it, sighing, shrugging, pretending it is tragic, and not systematic.

Tshiamo and Baleseng are gone. Their names now belong to the litany of ghosts: Karabo Mokoena, Reeva Steenkamp, Tshegofatso Pule, Namhla Mtwa. Their absence...a mirror to the nation's failure. Their deaths...a reminder that South Africa is not merely in crisis — it is in denial.

And denial, as it turns out, is just another word for murder.

Khumalo is an independent columnist and a former newspaper editor.